We’ve all experienced some kind of assumption made about us based on our birth order, right? I’m the oldest of two and because of that, people seem to think I have my life in order (which I don’t). As it turns out, there’s a lot of science to back up most of these assumptions. But, that doesn’t mean that they are always true. There are still a lot of exceptions to the rules.

Human behavior is determined not fully by concrete, formulaic systems. It is determined by free will, something that cannot ever be completely predicted by science. In Dr. Frank J. Sulloway’s book, Born to Rebel, he meticulously outlines human behavior through scientific methods, but even he still admits that there are exceptions to his findings. Human behavior is simply too complex and open-ended to be able to conclusively predict someone’s behavior based simply on his or her birth order. Even the most well-known written work on birth order (Born to Rebel) can’t conclusively predict human behavior.

Functional Birth Order

Before we jump into Sulloway’s observations on the birth order and personality relationship, we have to define “functional birth order”. This is the birth order Sulloway focuses on throughout the book and he defines it as “chang[ing] owing to sibling mortality, adoption, remarriage, and other circumstances” (Sulloway 22).

So if a kid is biologically the fourth child and they are adopted into another family which already has one other child, or if two of their older siblings die, they functionally become the second child. Sulloway notes that functional birth order changes a child personality into a new birth order category, but only if the child is still young enough (Sulloway 22). For example, if as teenagers, the firstborn of two dies, the laterborn functionally becomes the firstborn, but their personality will likely not be affected in terms of birth order categories.

Sulloway’s Observations

According to Sulloway, firstborns are “more responsible and achievement oriented” (Sulloway 55), are more assertive and dominant (69), and more emotionally intense, meaning they are “slower to recover from upsets” (70). Basically, we’re really good at holding grudges. Sulloway also notes that only-children or “singletons…are typically closer to firstborns” because both groups “tend to identify with parents and authority” (23).

In general, firstborns seek favor from their parents, therefore will excel in school and be the “responsible” child to please them (Sulloway 69).

Laterborns, on the other hand, “are more inclined than firstborns to question authority and to resist pressure to conform…” (Sulloway 70). They “should” be more open to new experiences than firstborns (Sulloway 70), and are “more socially successful” (55).

Sullowayuses “laterborns” as a catch-all term for any child born after the first. He provides extremely little evidence for any sort of difference between middle-children and last-born children. Throughout the book, Sulloway uses ‘firstborn’ and ‘laterborn’ as the two categories for differing personality traits.

Darwinian Support

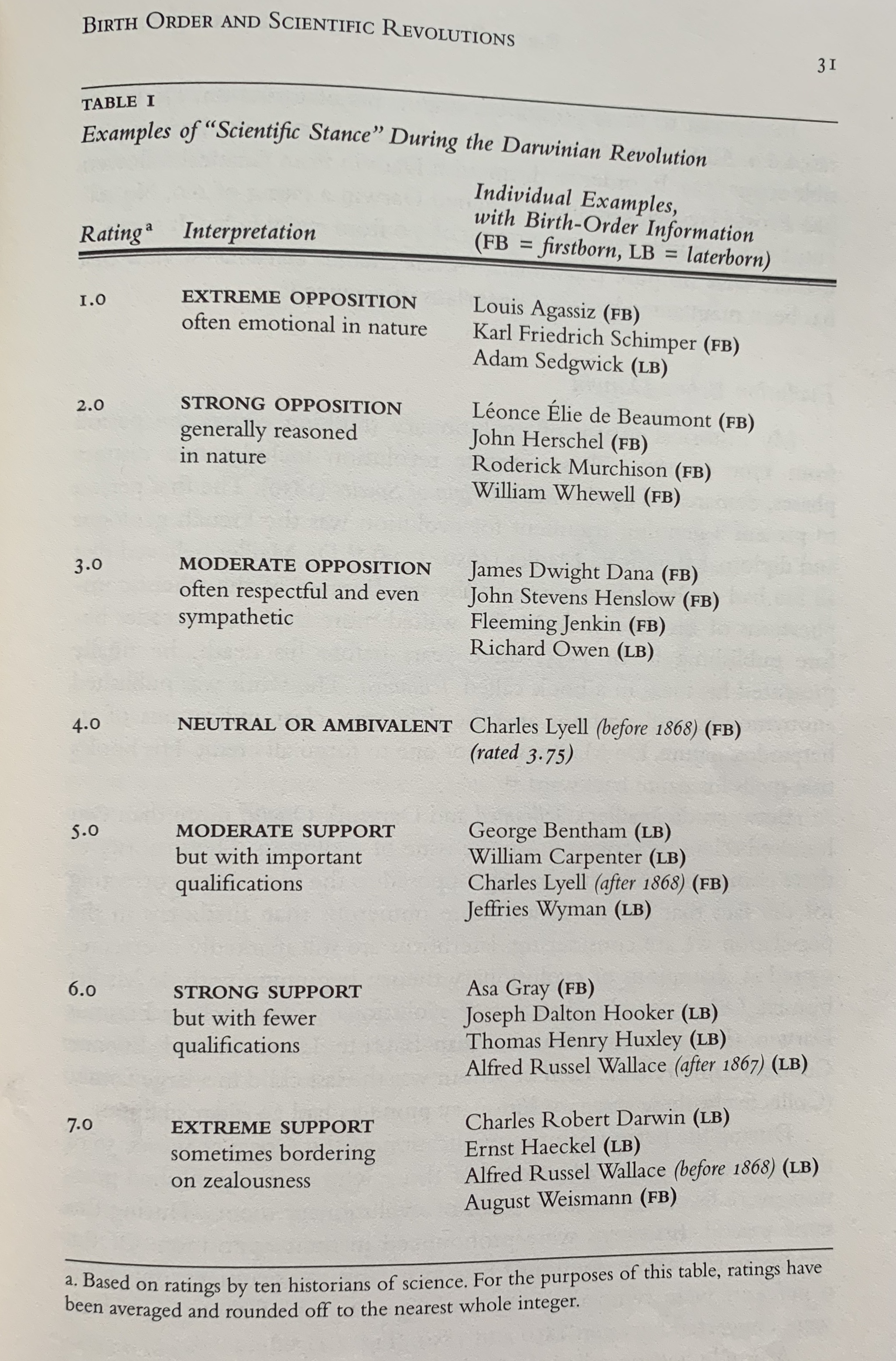

Continuing with his theme of analyzing birth order personality traits in relation to scientific innovation, Sulloway compiles a collection of people throughout history who have vocalized their support for or distaste of “the Darwinian Revolution”. For the most part, firstborns tended to oppose the ideas Darwin put forth about evolution and laterborns tended to support him, but there are a few notable exceptions.

We can see that Adam Sedgwick, a laterborn, falls under the “extreme opposition” category, while Asa Gray and August Weismann, both firstborns, fall under the “strong support” and “extreme support” categories, respectively (Sulloway 31). These three people go exactly against what Sulloway would expect them to based solely on their birth orders.

Sulloway’s “Variables”

In the introduction to the book, Sulloway writes, “Human behavior is predictable, but only when the context has been adequately specified” (XVII). It becomes glaringly obvious, just from reading Born to Rebel itself, that predicting human behavior from any perspective is an extremely complex undertaking.

Sullowayspends a lot of time discussing these exceptions. In fact, he dedicates an entire chapter to addressing them. In chapter 8, “Exceptions to the Rule”, Sulloway lists many influences other than birth order that have been proven to influence personality as well. In Table 5, “Parent-offspring conflict… Sibship size… Gender… Age gaps … Age at parental loss… Social class… [and] Temperament” are all listed as “Predictors” of behavior (Sulloway 197). Table 6 lists 9 different variables which may lead to exceptions in predictions about one’s radicalism based on birth order: “Social attitudes… parental social attitudes… parental birth orders… age… personal influences… national styles… social class… interpersonal rivalry… [and] scientific evidence” (Sulloway 213). Almost all of the variables listed in Table 6 are based on personal free thought and experience, which birth order does not determine.

Predicting how these variables will affect someone’s behavior can be difficult, as well. Sulloway uses the relationship between Robert FitzRoy and Charles Darwin as an example of how these additional variables can be tricky. Sulloway asks, “How could a man who for five years shared his Beagle cabin with Charles Darwin have later opposed Darwin’s theories?” (206). In fact, Sulloway predicted FitzRoy’s probability of supporting Darwin as 66% using the same method he used to categorize support and opposition back on page 31 (206). Though FitzRoy had maintained a close friendship with Darwin on the voyage to the Galapagos Islands, in the end, it seems to be his “political opinions” and “religious conversion” which undermined the friendship and caused FitzRoy to oppose Darwin’s conclusions(207). His personal life experience and free-will caused FitzRoy’s behavior to rebel against proper predictions.

The Unpredictability of Human Behavior

According to Professor Albert-László Barabási at Northeastern University, and his research team, “human behavior is 93 percent predictable” according to research on human travel patterns (PhysOrg.com). And even though 93 percent may seem very accurate, there is still that 7 percent which remains unpredictable. And as we can see from the exceptions Sulloway provides in Born to Rebel, 93 percent is not enough to guarantee someone’s personality and future behavior based on their birth order.

Despite this observed 93 percent accuracy in predicting human behavior, there are significant challenges, even when it comes to machine learning prediction. In their essay, “Predicting human behavior: The next frontiers”, V.S Subrahmanianand Srijan Kumar list some of these challenges, including “rare-event prediction” and the “dynamically changing” nature of human behavior (Kumar et al.). When it comes to ‘rare events’, or exceptions, “machine learning algorithms have difficulty disambiguating the data on these ‘rare’ individuals”(Kumar et al.). Now, obviously, computers do not have human emotions. It is usually easier for humans to understand the reasoning behind these “‘rare’individuals”, through thinking through the situation emotionally. However, this does not change the fact that the outliers exist, therefore there must be some, or in the case of birth order analysis, many, outstanding variables which make some of the data unpredictable to some degree. And considering that “human behavior is dynamically changing” (Kumar et al.) adds another layer of complexity which makes it harder to predict.

The Subjectivity of Human Behavior

In an article titled “Birth order stereotypes and why they’re often wrong” by Ingela Ratledge, written for CNN, psychologists and authors of books on birth order expose some reasons behind birth order stereotypes proving to be incorrect.

The stereotype for firstborns, according to the article, is a “natural leader, ambitious, responsible” (Ratledge), which aligns with Sulloway’s findings. In fact, Ratledge even quotes Sulloway: “‘A 2007 study in Norway showed that firstborns had two to three more IQ points than the next child,’ says Frank J.Sulloway” (Ratledge). However, she goes on to explain one reason why this is not always true: “Parents can set high expectations for a first (or only) child” and when the child believes they cannot meet those expectations, they “‘may veer off in another direction’ says Kevin Leman, Ph.D., a psychologist and the author of The Birth Order Book” (Ratledge). Gaging whether a set of expectations are too high is completely subjective to the child’s own beliefs about how much they can handle and it would be different for every person. Variables like these are too nuanced, therefore would be very difficult to factor into a specific outline to determine personality based mainly upon birth order.

Ratledge goes on to the stereotypes for “the baby”, or the lastborn, which include “freespirit, risk taker, charming” (Ratledge). However, again she brings up one situation in which this would be incorrect; she quotes Linda Campbell, a professor, saying, “Some babies resent not being taken seriously… They might become very responsible, like the oldest” (Ratledge). Again, this variable is subjective to the situation and relies on how the child feels, which is too nuanced to accurately be taken into account while studying birth order.

To finish the article, Ratledge lists “5 things that throw [birth orderstereotypes] all off”, most of which we’ve already seen: “Temperament… Gender…Physicality… Specialness… [and] Age spacing” (Ratledge). But before she gets into the list, she points out that “according to the White- CampbellPsychological Birth Order Inventory,” which tests how accurately people identify with their birth order category, “only 23 percent of women and 15 percent of men are a true match,” using the list to explain why (Ratledge).

Sulloway seems so confident in his assessment of how birth order affects lifelong personality, but as we can see from the statistics, the majority of people don’t truly match these categories. While we can all agree from personal experience and relationships that firstborns tend to be better in school and more “bossy”, and lastborns tend to be better at socializing, statistical evidence and an abundance of intricate, influential variables tell a different story. Human behavior is much too subjective and unpredictable.

At the end of the day, however, we cannot throw away this science. Birth order studies are endless because there is actually truth behind them. To ignore the science would be foolish, but to believe that it is conclusive in predicting personalities is foolish, too. I think the answer to our personalities lies somewhere in between.

Works Cited:

“Human behavior is 93 percent predictable, research shows.” PhysOrg, 23 Feb. 2010, https://phys.org/news/2010-02-human-behavior-percent.html. Accessed 19 Nov. 2018.

Kumar, Srijan and V.S. Subrahmanian. “Predicting human behavior: The next frontiers.” Science, 3 Feb. 2017, http://science.sciencemag.org/content/355/6324/489. Accessed 19 Nov 2018.

Ratledge, Ingela.“Birth order stereotypes and why they’re often wrong.” CNN, 18 June 2015, https://www.cnn.com/2015/06/18/health/birth-order/index.html. Accessed 19 Nov. 2018.

Sulloway, Frank J. Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives. Vintage, 1997.